USING FMRI TO ASSESS BRAIN ACTIVITY IN PEOPLE WITH DOWN’S SYNDROME

1Aqib Rashid Parray*, 2Arshad Alam Khan, 2Ashita Jain, 3Subhamoy Satpathy, 4Myasar Ahad

1Assistant Professor, Department of Allied Health Science, Brainware University, Kolkata, India

2Assistant professor, Department of Paramedical Science, Faculty of Allied Health Science, SGT University India.

3Chief Radiographer, Brainware Diagnostic and Research Centre, Brainware University, Kolkata, India

4M. Sc. Clinical Psychology, SGT University, Gurugram, Haryana, India

ABSTRACT

Background: The main purpose of using fMRI in people with Down’s Syndrome is to find variations in Brian activation and connectivity patterns compared to typically developing individuals. This can help us to identify which brain areas are affected and how they function differently from normal people fMRI helps us in the early detection of cognitive and neurological problems in individuals with DS. Methodology: This descriptive study is based on a review of the literature. A literature review analysis was carried out Using several suggested platforms, including PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Science, etc. Result: People with DS displayed distinct activation patterns that were not observed in people with. These differences can be related to various cognitive functions such as memory, language processing, and problem-solving. DS patients showed noticeably smaller magnitudes of temporal activations in language-related brain areas. Conclusion: The study on DS has benefited greatly from the application of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which has shed light on the neurological foundations of this complicated genetic disorder. FMRI has become a valuable tool for grasping the anatomical and functional variations in the brains of people with DS, providing insight into the behavioural and cognitive difficulties they encounter.

Keywords: fMRI, Down’s Syndrome, Bold Oxygen Level Dependent, Cognitive Process

INTRODUCTION

The method of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is utilized to observe brain activity by identifying alterations linked to blood circulation. The technique depends on the connection between the flow of blood in the brain and the activation of neurons when a specific area of the brain is active, there is an increase in blood flow to that region. The primary method used in fMRI is the utilization of blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) contrast, which was identified by Seiji Ogawa in 1990 this enables the visualization of neural activity in the brain or spinal cord of humans and other animals by capturing the changes in blood flow associated with energy consumption by brain cells [1]. The cortex experiences increased neural activity, leading to a greater local blood flow to meet the heightened need for oxygen and other essential substances at the capillary level, it's noteworthy that the rise in blood flow exceeds the necessary amount, leading to a surplus of oxygenated arterial blood compared to deoxygenated venous blood [2]. Functional MRI research involves two primary methodologies: task-based fMRI and resting-state fMRI. Each method offers unique insights into brain function and has its own set of applications and advantages. Task-Based fMRI: Task-based fMRI involves Observing brain activity occurs when an individual engages in a specific cognitive, sensory, or motor task. Resting-state fMRI: Resting-state fMRI, on the other hand, explores the natural functional connections of the brain by identifying spontaneous changes in the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal while individuals are at rest [3].

When routine brain scans are conducted, it is typically assumed that the signal intensity within each voxel stays constant over time. However, in fMRI imaging, the signal intensity is expected to fluctuate during the scan as the patient participates in a specific task or paradigm. MR anatomic imaging sequences usually take 3 to 4 minutes to capture images of the body's structure. In contrast, fMRI imaging quickly scans the entire brain multiple times in just 1 to 4 seconds. This enables the detection of changes in signal intensity over short time periods. The longer acquisition time of anatomic MR imaging allows for the capture of high-resolution images with a matrix size of 256 x 256 or higher.

|

Corresponding Author: Aqib Rashid Parray, Assistant Professor, Department of Allied Health Science, Brainware University, Kolkata (WB) India. Email: aqibparray78@gmail.com |

Conversely, fMRI imaging typically acquires images using a smaller matrix size of 64 x 64 [4]. however, it’s not without the limitation one of the main limitations of fMRI is that it indirectly measures neural activity instead of directly measuring it [5]. Down’s Syndrome (DS), also referred to as trisomy 21, is a genetic condition defined by the occurrence of an extra chromosome in individuals from birth. Generally, humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes in each cell, totalling 46 chromosomes individuals with DS have an extra copy of chromosome 21, leading to a total of 47 chromosomes in their cells. This change in chromosomal makeup has a substantial impact on the development of their brain and body [6] Studies suggest that Down syndrome can result from three different types of chromosomal changes. The primary cause is complete trisomy 21, with the majority of Down syndrome cases being attributed to this type. Another type is mosaic trisomy 21, which represents a small percentage (less than 5%) of Down syndrome cases. The third type, translocation trisomy 21, involves the presence of only a portion of an extra copy of chromosome 21 in the cells and accounts for a small number of DS cases [7]. People with Down syndrome display a wide variety of signs and symptoms, such as intellectual and developmental disabilities, neurological characteristics, congenital heart issues, gastrointestinal irregularities, unique facial features, and other anomalies [8]. India has the highest number of people affected by DS worldwide the numbers are worrying, but what's even more alarming is that this condition leads to fatalities in India due to neglect, lack of awareness, and outdated medical and technological resources. DS affects approximately 23,000 to 29,000 new borns in India every year [9].

AIM AND OBJECTIVE

Aim: Assessment of Brain Activity Using fMRI in Individuals with Down Syndrome: A Review Study

Objective

- Analysing signals from different parts of the brain in people with Down’s syndrome through fMRI?

- Correlation of Alzheimer’s diseases and Down syndrome in people based on the diagnosis of fMRI?

- Analysing different brain activation patterns and connections through task-based and resting state fMRI

METHODOLOGY

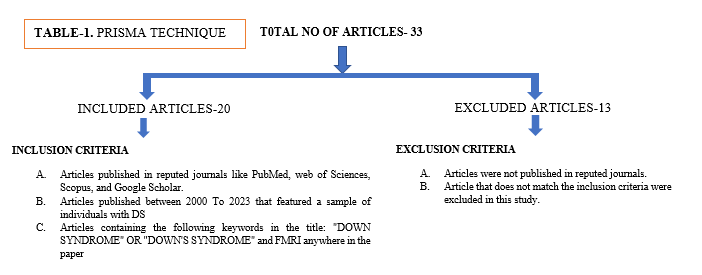

This descriptive study is based on a review of the literature. A literature review analysis was carried out using several suggested platforms, including PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Science, etc. The original English-language research articles for evaluating the brain activity of individuals with DS were gathered and examined. The PRISMA approach was used in 20 out of the 33 original articles that met the inclusion criteria were examined. The following standards for inclusion were used. The publications were to be original fMRI studies published between 2000 and 2023 that featured a sample of individuals with DS. Papers containing the following keywords in the title: "DOWN SYNDROME" OR "DOWN'S SYNDROME" and FMRI anywhere in the paper A study providing qualitative information regarding FMRI to assess brain activity in people with Down’s syndrome was included in a review literature-based study. This study has been performed in the Department of Radio-Diagnosis & Imaging at SGT Medical College, Hospital & Research Institute from July 2023 to December 2023.

DISCUSSION AND RESULT

The use of high-resolution 7T MRI imaging in people with DS, provides insight into several characteristics of the hippocampal structure. Selective volume reductions were observed in the bilateral hippocampus subfields of cornu Ammonis field [10], dentate gyrus, and tail. The study also looked into how functionally connected the hippocampi are in people with Down syndrome. It discovered broad declines in connection strength, mostly to frontal areas. This change in functional connectivity to frontal areas is important because it affects hippocampal-dependent cognitive processes like memory and executive skills. Since people with DS are more likely to have Alzheimer's disease, it is important to develop strategies and changes in order to create techniques that may be able to prevent or treat Alzheimer's disease in people with DS [11].

During the imaging, the participants viewed cartoons, and their brain activations were assessed in response to specific characters (protagonist and antagonist), violence, and auditory and visual elements. The dorsal attention network of the brain and its reaction to the cartoons' violent and thematic elements were the main areas of study [12]. The study discovered several significant variations in brain activation between people with DS and others who are usually developing. Dorsal Attention Network was busiest in normally developing people during cartoon violence sequences. On the other hand, during violent scenarios, people with DS showed noticeably less activation in this network [13]. People with DS showed noticeably reduced activation in their left medial temporal lobe when the antagonist was present. The attentional brain activation differences between persons with Down syndrome and normally developing individuals grew when the cartoon scenarios depicted more relative threats. People with DS showed markedly less activation in their primary sensory cortices, which may affect how they react to more complicated social cues, such as violent acts [15].

According to the study, as compared to normally developing (TD) controls, those with DS show higher levels of between-network connection in multiple network pairs. More specifically, a significant boost in connection was seen in six out of 21 network pairs [16]. These network pairs comprised DAN-Frontoparietal, DAN-DMN, Limbic-DMN, Somatomotor-Frontoparietal, and Somatomotor-DMN. Differences in Within-Network Connectivity: Although DS changed the Between-Network Connectivity, there were no notable changes in Within-Network Connectivity [17]. Resting state functional connectivity is used to check brain functions at resting state Because subjects are not brain functions at resting state performing any particular activities while they are at rest, researchers are able to look at spontaneous neural activity and the functional connections between various brain regions. The connection patterns between people with DS, William Syndrome, and usually developing controls may be shown by RSFC analysis. For example, people with DS may show abnormal connectivity in areas related to memory and language processing, while people with WS may show abnormal connectivity in areas related to social cognition. The results might have effects on therapies as well. It may be feasible to create tailored therapies or interventions that try to alter brain connections in order to enhance cognitive and behavioural outcomes in people with DS or WS if particular RSFC patterns are found [18].

One of the main results was that in comparison to Typically developing (TD) individuals, DS patients showed noticeably smaller magnitudes of temporal activations in language-related brain areas. These areas included the middle and superior temporal gyri, which are important for language comprehension. The reduced activation raises the possibility of cellular brain dysfunction or connection problems, which could be a factor in the language-related behavioral deficiencies seen in DS. The study discovered that although TD people had distinct activation patterns for both forward and backward speech, DS people had nearly the same activation patterns under both circumstances. This implies that people with Down syndrome might find it difficult to selectively activate various brain networks for speech and non-speech sounds. People with DS displayed distinct activation patterns that were not observed in people with TD. These included the precuneus, superior parietal lobule, and anterior and posterior cingulate gyrus. Higher attentional demand in DS patients is suggested by the attention-related activation in the cingulate cortex, which may be brought on by challenging tasks. It's interesting to note the distinct activation in the parietal lobes, which are linked to visuospatial processing and visual attention. Due to aberrant functional connections during brain development, people with DS may rely more on visualization for auditory language processing as a compensatory strategy, given the relative preservation of grey matter in these areas [19].

Using structural equation models using resting-state fMRI data is a useful method for examining dynamic effective connectivity networks in people with Down syndrome. The discovery of altered patterns of connection in people with Down syndrome provides insight into the neurological underpinnings of variations in cognition and perception. These findings advance our knowledge of the aberrant neurodevelopment linked to Down syndrome. Researchers and clinicians can create tailored strategies to improve cognitive results and quality of life for individuals with Down syndrome by detecting particular abnormalities in connection. Structural equations models showed that the dynamic effective connection networks of the control group and the DS group differed significantly. Individuals with Down syndrome (DS) had modified network patterns, indicating variations in the interactions between various brain regions when at rest. These results indicate abnormal neurodevelopment in DS patients. The disrupted connection may affect the information flow between brain regions involved in different cognitive functions, which could exacerbate cognitive impairments. The results of this study imply that the cognitive and behavioural traits of Down syndrome are linked to an abnormal degree of centrality and functional connectivity in affected people. Specific brain regions exhibit altered connection patterns that could reveal information about the neural mechanisms causing cognitive deficiencies associated with Down syndrome and serve as possible targets for interventions or therapies [19]. Two distinct RS-fMRI techniques were used in the study Regional homogeneity (ReHo) and fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (fALFF). Significant differences in spontaneous brain activity were seen between DS patients and TD control subjects in the study. The fALFF analysis revealed that some areas of the frontal and temporal lobes as well as the left anterior cerebellar lobe had higher activity in DS. The left limbic lobe, left posterior cerebellar lobe, left parietal and occipital lobe, and left limbic lobe were the areas in DS with less activity than in controls.DS subjects displayed enhanced activity in certain regions of the inferior temporal lobe, left rectus, and left frontal lobe in the ReHo study. Both the right limbic lobe and the frontal lobe showed decreased activity. The regions exhibiting variations in fALFF and ReHo and cognitive tests showed a strong association. This shows that the cognitive characteristics of the two groups were closely associated with the variations between the DS and TD controls.

These associations provided credence to the hypothesis that the cognitive abilities of DS participants particularly their verbal and nonverbal intelligence may be correlated with either increased or decreased activity in particular brain regions. Persons with DS may have different spontaneous brain activity as a coping strategy for their impaired neural networks and cognitive processes. Other illnesses including cognitive deficits have also been shown to have this compensating mechanism. The findings of the study are consistent with the structural brain abnormalities associated with Down syndrome (DS), which mostly impact areas of the brain such as the frontal, temporal, parietal, and cerebellar. Additionally, anomalies were noted in the default mode network (DMN). The results shed light on possible amyloid deposition in young DS patients and suggest that AD-related pathology may already exist. The strong relationship found between the changed brain activity and cognitive results suggests that the variations in brain activity seen in DS patients are directly related to cognitive characteristics [20].

A group of individuals with DS was selected for participation in the study, and they were divided into two groups: the experimental group and the control group. The experimental group underwent a computerized visual perceptual training program, while the control group did not receive any specific intervention. To measure changes in brain activity, both groups underwent fMRI scans before and after the intervention. The researchers utilized standardized assessments to evaluate visual perceptual abilities and cognitive functioning before and following the intervention. The experimental group demonstrated significant enhancements in visual perceptual abilities in comparison to the control group. These findings suggest that the computerized training program effectively improved visual perception skills among individuals with DS. Changes in brain activity were evident in the fMRI scans of the experimental group post-training. Specifically, there was heightened activation in brain regions linked to visual processing and cognitive functioning. This indicates that the training program not only enhanced perceptual skills but also induced alterations in neural pathways associated with these functions. The enhancements in visual perceptual abilities were not limited to tasks directly related to the training program but also extended to other areas of cognitive functioning. This suggests that the benefits of the training program may have a broader impact on cognitive functioning in individuals with DS Although the study focused on immediate post-training effects, the long-term sustainability of the improvements remains unexplored. Further research is necessary to determine whether the gains in visual perceptual abilities endure over time or if additional booster sessions are required to maintain the benefits [14].

Future studies may build upon these findings to develop targeted interventions to improve cognitive and behavioral outcomes for individuals additionally, longitudinal fMRI studies offer a powerful approach to unraveling the dynamic changes in brain function and connectivity over time fMRI studies can be done during task performance to understand brain changes in DS people. People with DS can’t respond to the threat of violence, fMRI can be done to show them threatening violence continuously through MR-friendly VR Goggles to see how the brain responds to these scenes and which brain part is compromised [21] [22].

CONCLUSION

The study on DS has benefited greatly from the application of fMRI, which has shed light on the neurological foundations of this complicated genetic disorder fMRI has become a valuable tool for grasping the anatomical and functional variations in the brains of people with DS, providing insight into the behavioural and cognitive difficulties they encounter fMRI study revealed that people with DS frequently have different brain activation patterns and connections, which can be linked to a range of cognitive deficits. With the help of this technology, it has been possible to pinpoint the afflicted brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus, and gain a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the cognitive deficits and memory impairments that affect people with DS. Using fMRI in Down syndrome may help us understand the condition better and pave the way for the creation of novel treatments and interventions. The people with DS relative deficiency in perception and reaction to violence. This deficiency may be linked to decreased activation in specific brain areas that handle threats and altered sensory perception.

REFERENCES

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024, November 17). Functional magnetic resonance imaging. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Functional_magnetic_resonance_imaging.

- Gore, J. C. (2003). Principles and practice of functional MRI of the human brain. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 112(1), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI20031901.

- Huettel, S. A. (2010). Functional MRI (fMRI). In Encyclopedia of Spectroscopy and Spectrometry (pp. 741–748). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374413-5.00053-1.

- Sopich, N., & Holodny, A. I. (2021). Introduction to functional mr imaging. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America, 31(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nic.2020.09.002

- Glover, G. H. (2011). Overview of functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurgery Clinics of North America, 22(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nec.2010.11.001

- Down syndrome: Symptoms & causes. (n.d.). Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved March 19, 2024, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17818-down-syndrome

- What causes down syndrome? | nichd - eunice kennedy shriver national institute of child health and Human Development. (2024, February 16). https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/down/conditioninfo/causes

- Akhtar, F., & Bokhari, S. R. A. (2024). Down syndrome. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526016/

- Jerajani, D. (2022, March 7). State of down syndrome in india: Facts & figures. PharmEasy Blog. https://pharmeasy.in/blog/down-syndrome-bringing-the-nation-down/

- Cañete-Massé, C., Peró-Cebollero, M., & Guàrdia-Olmos, J. (2020). Using fMRI to assess brain activity in people with Down syndrome: A systematic review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 14, 147. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2020.00147

- Koenig, K. A., Oh, S.-H., Stasko, M. R., Roth, E. C., Taylor, H. G., Ruedrich, S., Wang, Z. I., Leverenz, J. B., & Costa, A. C. S. (2021). High-resolution structural and functional MRI of the hippocampus in young adults with Down syndrome. Brain Communications, 3(2), fcab088. https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcab088

- Jacola, L. M., Byars, A. W., Chalfonte-Evans, M., Schmithorst, V. J., Hickey, F., Patterson, B., Hotze, S., Vannest, J., Chiu, C.-Y., Holland, S. K., & Schapiro, M. B. (2011). Functional magnetic resonance imaging of cognitive processing in young adults with down syndrome. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 116(5), 344–359. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-116.5.344

- Reynolds Losin, E. A., Rivera, S. M., O’Hare, E. D., Sowell, E. R., & Pinter, J. D. (2009). Abnormal fmri activation pattern during story listening in individuals with down syndrome. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 114(5), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-114.5.369

- Wan, Y.-T., Chiang, C.-S., Chen, S. C.-J., & Wuang, Y.-P. (2017). The effectiveness of the computerized visual perceptual training program on individuals with Down syndrome: An fMRI study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 66, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.04.015

- Anderson, J. S., Treiman, S. M., Ferguson, M. A., Nielsen, J. A., Edgin, J. O., Dai, L., Gerig, G., & Korenberg, J. R. (2015). Violence: Heightened brain attentional network response is selectively muted in Down syndrome. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 7(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11689-015-9112-y

- Cañete-Massé, C., Carbó-Carreté, M., Peró-Cebollero, M., Cui, S.-X., Yan, C.-G., & Guàrdia-Olmos, J. (2023). Abnormal degree centrality and functional connectivity in Down syndrome: A resting-state fMRI study. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 23(1), 100341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2022.100341

- Anderson, J. S., Nielsen, J. A., Ferguson, M. A., Burback, M. C., Cox, E. T., Dai, L., Gerig, G., Edgin, J. O., & Korenberg, J. R. (2013). Abnormal brain synchrony in Down Syndrome. NeuroImage: Clinical, 2, 703–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2013.05.006

- Vega, J. N., Hohman, T. J., Pryweller, J. R., Dykens, E. M., & Thornton-Wells, T. A. (2015). Resting-state functional connectivity in individuals with down syndrome and williams syndrome compared with typically developing controls. Brain Connectivity, 5(8), 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1089/brain.2014.0266

- Figueroa-Jiménez, M. D., Cañete-Massé, C., Carbó-Carreté, M., Zarabozo-Hurtado, D., & Guàrdia-Olmos, J. (2021). Structural equation models to estimate dynamic effective connectivity networks in resting fMRI. A comparison between individuals with Down syndrome and controls. Behavioural Brain Research, 405, 113188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2021.113188

- Cañete-Massé, C., Carbó-Carreté, M., Peró-Cebollero, M., Cui, S.-X., Yan, C.-G., & Guàrdia-Olmos, J. (2022). Altered spontaneous brain activity in Down syndrome and its relation with cognitive outcome. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 15410. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19627-1

- Singh, R. K., & Kumar, A. (2024). Advancements in Medical Imaging: Enhancing Diagnostic Precision and Patient Care. Innovative Journal of Medical Imaging, 1-4, https://doi.org/10.62502/ijmi/s6jhv519

- Jha, P. K. (2024). Radiomics and Machine Learning in tumor Characterization and Treatment Planning. Innovative Journal of Medical Imaging, 1-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.62502/ijmi/hb03ba79